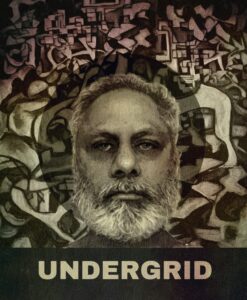

Sanjay Sahgal is a forensic psychiatrist who creates strange and brilliant cartoons on ShadowToons.com. He also writes essays, satire, and most recently a two-thousand-word comment on my Persophone Images. I wanted to make sure other Undergrid readers didn’t miss it, so I am publishing it as its own blog article here.

Sanjay flatters both me and the drawings (he is an old, dear friend who would support me and applaud stick figure drawings if I chose to publish them,) but I think it is a great example of a simple writing prompt (the images) leading to creativity and reverie. As he puts it, “images (even with titles) are like dreams and the viewer of the image can find and experience multiple meanings and emotions respectively, occasionally even contradictory meanings and emotions existing simultaneously.”

Sanjay writes:

There is so much to admire about these images.

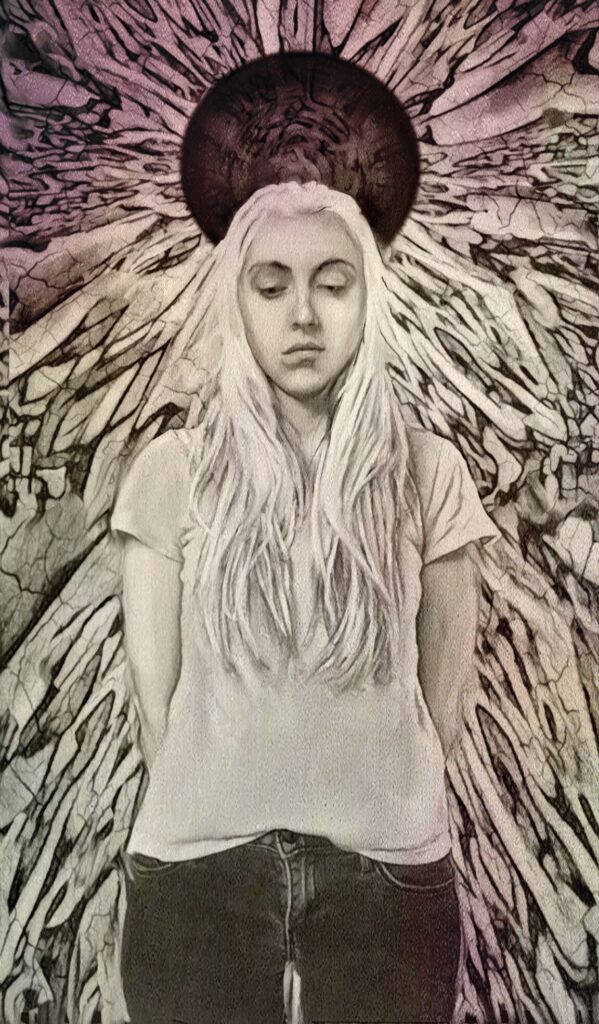

First, the images themselves each convey an unsettling sense of entrapment. In Persephone Falling, the subject (assume to in some way reverberate with the myth of the cursed Persephone) is in a state of apparent resignation and fatigue. She is trapped, if appears, with no sound way to escape: the visceral organic linings resemble a stomach and the “only way out” a birth canal. However, it is the other end a birth canal. Unlike typical humans, who are “stuck” in organic traps of wombs and destined to be released through the birth canal into the open sunlit world, in the first image the subject seems to have experienced a kind of contrapositive of this standard stage in human reproduction. Visually, she appears to have come through the birth canal INTO a trapped, organic womb/captive-space. Unlike infants who exit the birth canal and cry tears of intoxicated new arrival into a world of suffering the nature of which they are innocent, this subject appears to exit the birth canal, resigned and tearless, into a seemingly safer but isolate world of organic darkness.

In Persephone Reverie, the subject is lit, but lit from below. What would more typically be the source of light (an orb high and above her head) is more of an absorber of light from a different source. The expression of the subject suggests a gratitude or longing for the source of light coming up from beneath her. But with her hands behind her back and her mouth signaling melancholy, it’s as if she has been here before, that she knows that the light won’t bring her lasting joy, that she knows what comes next and it’s as if she is trapped again.

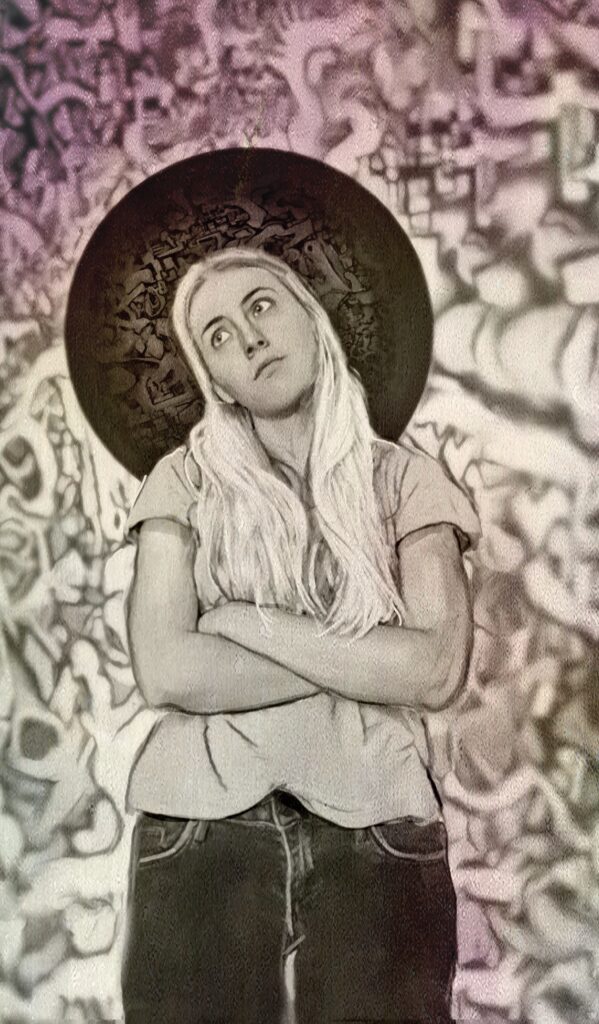

The third image is perhaps the one with the subject having the most visually interpretable facial expression and posture. Her rolled eyes and crossed arms clearly signal a frustrated resignation, a sense of “here we go again”, a sense of powerlessness but not fear. Fatigue and lack of hope but not danger. Again the flood of light comes from below, stronger in intensity, and the orb-that-would-typically-be the-sun looks like a kind of sponge, not even reflecting but absorbing the light. It also can be seen as a dark halo, marking not the blessed or sacred but the cursed or defiled. The tile of Persephone Lost along with this imagery suggests that the subject is not lost in the sense of not knowing where she is or how to get back home but lost in the sense of a “lost cause” or a lost game.

It may be a coincidence that subject’s name is Persephone (I don’t know what the subject’s name is nor am I certain if the subject is “real” or an amalgam of a few models or even a creation of the artist’s imagination). But let’s choose to take the name to be integral to the images and see where meanings can unfold. After all, even if the subject’s name happens to be Persephone without any reference to the myth (I once met a woman in her 20’s named Cassandra who had no idea that her name referenced a mythological character who was cursed to tell the truth but never be believed, for example), the viewer of the work does incorporate the myth of Persephone into the images. The viewer has no choice really. The name is not common. For example, the name isn’t Helen, which is a common enough contemporary name such that it might be stretch for a viewer to apply significance to the name (as in harkening back to the mythology of Helen of Troy).

No. Persephone is too dense with meaning as a name. Reviewing the myth, Persephone was a child born of incest between the gods (Zeus and his sister Damater). That’s enough for any god or human to bear but it then so happened that, at the age of sexual majority, her paternal uncle, Zeus’s brother Hades, “abducts” her. The myth is careful to point out that this word, “abduction” is a euphemism the purpose of which is misdirection, that is, Zeus was indeed aware of Hades’s plan and permitted it to occur. So we have a daughter born out of incest who is tacitly given to her father’s brother for sexual congress. Moreover, that brother, Hades, just happens to live in a realm of complete darkness—the underworld, the world of the dead. It is only Damater’s nagging that get’s Zeus to request that Hades return his daughter. At this point, Persephone is no more than an object for her immortal parent gods to bicker over. Hades, the weaker of the two brothers but also the one with the shitty job of ruling over the land of darkness, despair, and death, is not threatened but asked by Zeus, at the urging of Damater, to return the daughter Persephone to the sunlight of Olympus. Hades considers and, being relatively reasonable, agrees to return Persephone so long as she hasn’t eaten or drunk anything while captive in the underworld. What an odd criterion? Surely even the daughter of the gods has to eat or drink. It turns out to be the case that Persephone, not content with her plight as Hades’s captive, manages to limit her food intake to just 6 pomegranate seeds.

Zeus is like: “what the fuck do I do now?” Damater on the one hand is pestering him and making him feel guilty for permitting their incestuously conceived daughter to be taken into the underworld by Hades and, well, Hades is now partially-committed to the “abduction”. After all, Persephone did eat 6 pomegranate seeds in the underworld and so the underworld (seeds no less) is permanently a part of her.

So, as if Persephone were a toy without agency, Zeus concludes that Persephone will spend 6 months, one for each seed consumed un the dark underworld, seeds that are now a part of her, with Hades but also that she can spend 6 months (the remainder of the year) in Olympus in the open sunlight apparently delighting her mother, Damater. The myth is such that Persephone’s feelings and agency about the whole drama, which was sparked by her transition from child to womanhood, are discounted in Zeus’s judgment and decision.

And thus Persephone spends half her life in utter darkness with Hades and half her life in a sunlit world on the peaks of Olympus, all the while being aware that her cyclical eternal curse is the result of petty and egoic machinations of her incestuous parents and her uncle.

There are many ways to view this myth. Most often scholars associate it with the wheat harvest/cycle, which produces sunlight wheat fields half the year and degraded soil and starvation grounds for other half of the year.

These images, however, suggest something much deeper in the human collective psyche. Persephone (or the subject) is: 1) trapped in an unpleasant compromise arranged entirely by her egotistical parents and uncle; 2) seems to have no choice, to have been treated like an object in a trade rather than a sentient being with choices and inclinations of her own; 3) seems to be aware that what awaits her for the foreseeable future is an endless cyclical movement from light to dark, from fresh air to the stank of death, from one set of incestuous and egotistical parents to an equally self-preoccupied paternal uncle, all of whom view her more as an object to be moved and used than as a being with agency and choice.

With his background, the subject’s resignation, fatigue, sense of being trapped organically, and existence in a sort of upside down world where light comes from what is typically darkness (land, ground, holes, bedrock) and darkness comes from what is typically light (the sun or orb). it’s no wonder that the titles include falling, reverie, and lost. The subject is falling in that falling implies a lack of personal agency (in the most concrete terms it’s gravity that is in control but there are other more nuanced and metaphorical ways of falling). The subject is in reverie, which Cambridge Dictionary defines as “a state of being pleasantly lost in one’s thoughts” because, despite the whole fucked up arrangement imposed upon her, she does get sunlight half the time, even it is an imprisoned sunlight, a type of resigned and predictable comfort that lends itself to enjoying it while it lasts, to daydreaming because one knows in advance that the cycle of night/real-dreaming, the underworld of darkness, is going to take her under again soon. The subject is lost, once again, as in the use of the word similar to the phrased “a lost cause”. She knows where she is so she’s not lost literally. Indeed, quite the opposite, through repeated cycles over eons, Persephone knows exactly where she is at any give time. In this way, the title can be read as “lost” in the win/lost sense. Persephone lost. She didn’t win, which would be to have the freedom of choice and chance to forge her future like even mere mortal young women are most often offered. Instead, she lost because she has no choices. Her parents and uncle have fixed her life into a never-ending pendulum from darkness to light. It can easily be seen as a curse of sorts and the subject’s expressions in all three images contain strands of resignation, fatigue, defeat, and dare I say hopelessness? Persephone lost. Indeed, she wasn’t even given a chance to win the game. She lost by forfeit to the greater powers of her incestuous parents and unscrupulous paternal uncle, all three of whom were thinking of nothing but themselves and all three of whom offered Persephone no choices.

On a more present-day level, these three images capture something of what I personally see in young people today. Our generation has handed them a sort of Fate that resulted entirely from our egotistical preoccupations. No longer do young people have the basic gift of knowing that there will be an inhabitable earth bequeathed to them. No longer do they have the basic gift of some shred of true belief that democracy is a kind of ladder and that a touch of meritocracy is mixed into the American dream. Instead, they are handed a climate in crisis with no viable solution or even cooperation to find a solution in sight. Instead, they are handed an oligarchy cloaked as a democracy wherein they are given a future wherein, absent a civil war, the uber-wealthy will become wealthier and the thinning middle class will (in California at least) will pay (for now—it may get worse) 48cents on the dollar in Federal and State income taxes. They are given a world filled with existential hotspots—wars are always a part of the inheritance but this generation is inheriting wars AND 1000’s of hydrogen bombs owned by Russia, the USA, and even rogue military nations that are destitute and desperate like Pakistan. They can read as easily as any of their elders that the consensus of physicists and climatologists is that the detonation of even one hydrogen bomb in warfare (a hydrogen bomb is approximately 1000 times more powerful than the atom bombs dropped on two Japanese cities several decades ago) will more likely than not create a global “nuclear winter” and shift human social structures and survival in ways not yet imaginable.

Have we bequeathed our children the Fate of Persephone? Does the subject in each image convey the resignation, fatigue, anxiety, and hopelessness of most of today’s entering college freshmen? I see it. I see it in society but I also see this portrayed rather poignantly in these three related images.

Of course, images (even with titles) are like dreams and the viewer of the image can find and experience multiple meanings and emotions respectively, occasionally even contradictory meanings and emotions existing simultaneously. However, pondering these three images, this is what comes to my consciousness.

By Sanjay Sahgal