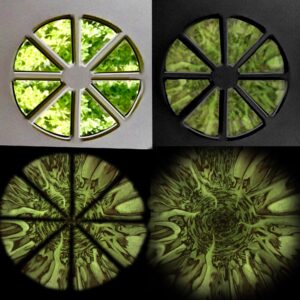

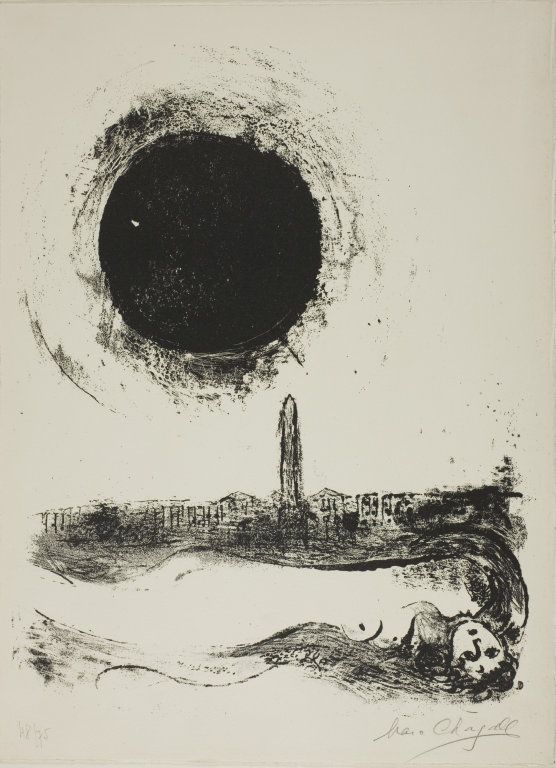

In the corner of my backyard out of view from the house, I have a ring of black stones that forms an imaginary well. Like a character from a Murakami novel, I often imagine climbing down to the dark bottom of that well, where I find all sorts of other spaces: caverns, chambers, libraries, and laboratories, as well as entire imaginary landscapes, usually beaches or lakesides, sometimes a yawning abyss. It feels like there is an entire cosmos down there, big enough to swallow galaxies like raindrops. The goal of this idle reverie is the Delphic maxim, “know thyself,” and we understand ourselves with metaphors of space.

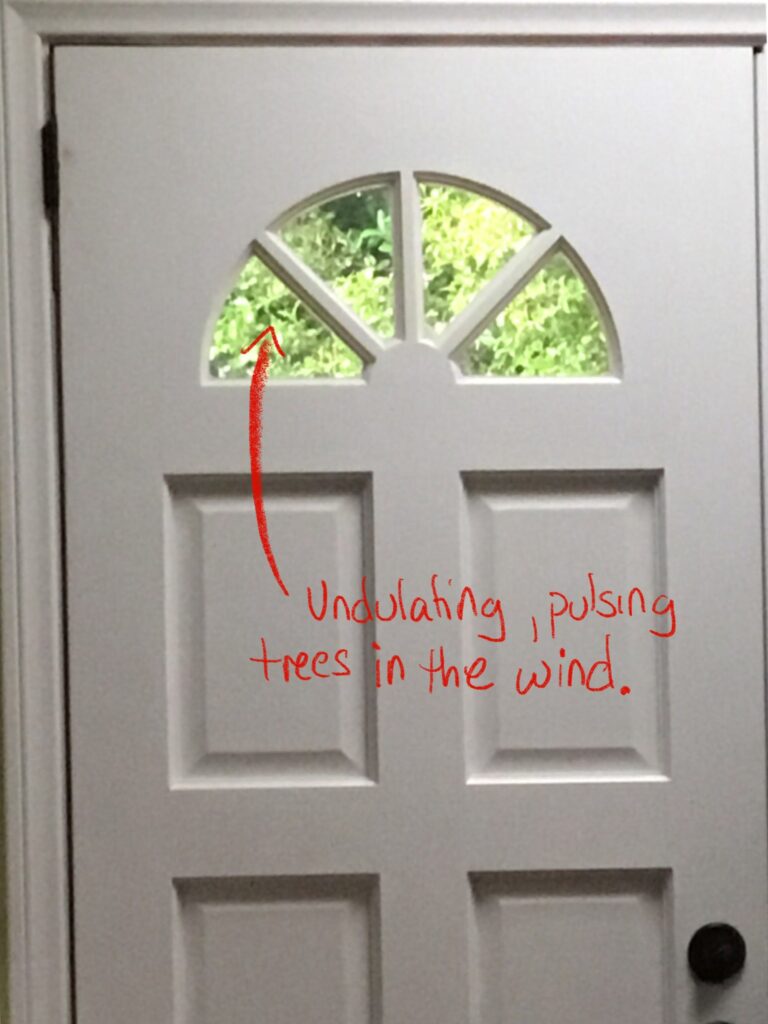

That is why my imaginary well (for others it may be a cellar, cave, or canyon) seems so deep. To look inward is to look down into depth. We imagine the unconscious as some subterranean chasm or fathomless ocean. Post-Jungian psychologist James Hillman writes, in The Dream and The Underworld, “The fundamental language of depth is neither feelings, nor persons, nor time and numbers. It is space. Depth presents itself foremost as psychic structures in spatial metaphors.” Among these metaphors, the ego is a house, the psyche is a labyrinth, and every dream is a mythological descent to the underworld. To dream, to be deep in thought, or to be deep in psychological analysis is to explore this inner geography.

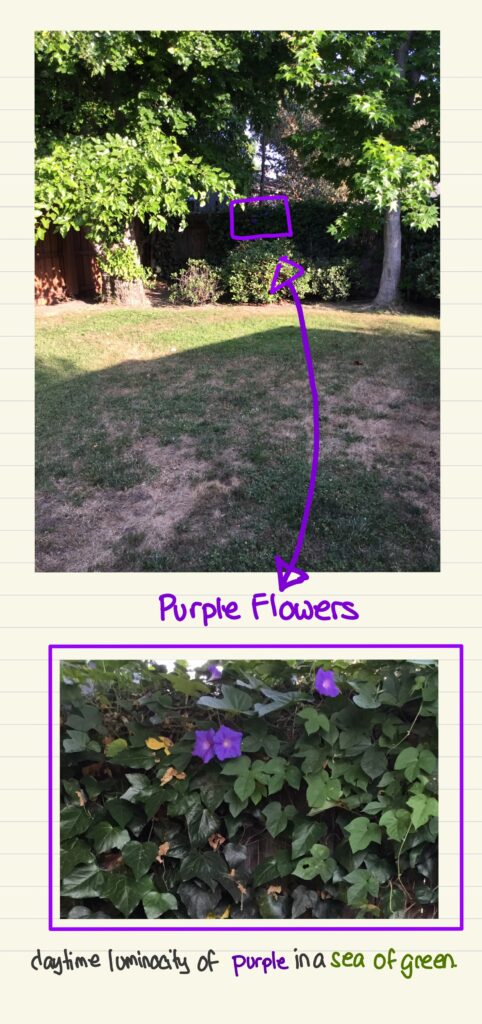

Within this massive space, our memories are tied to more intimate spaces, like kitchens, closets, and bedrooms. Gaston Bachelard writes, in The Poetics of Space, that the house we grew up in “is our corner of the world…. It is our first universe, a real cosmos in every sense of the word.” We never stop exploring “the universe of the house by means of thoughts and dreams” because to explore the material spaces—the musty attics, damp cellars, and winding corridors—is to explore ourselves. Every drawer, chest, and wardrobe is a container for memory, reverie, and imagination. The house itself is “the topography of our intimate being.” Our very identities are housed in the spaces we knew in childhood.

Thus, the maps we make of outer spaces give our inner worlds structure. Bachelard writes, “… over and beyond our memories, the house we were born in is physically inscribed within us. It is a group of organic habits. After twenty years, in spite of all the other anonymous stairways, we would recapture the reflexes of the ‘first stairway,’ we would not stumble on that rather high step. The house’s entire being would open up, faithful to our own being. We would push the door that creaks with the same gesture, we would find our way in the dark to the distant attic. The feel of the tiniest latch has remained in our hands.”

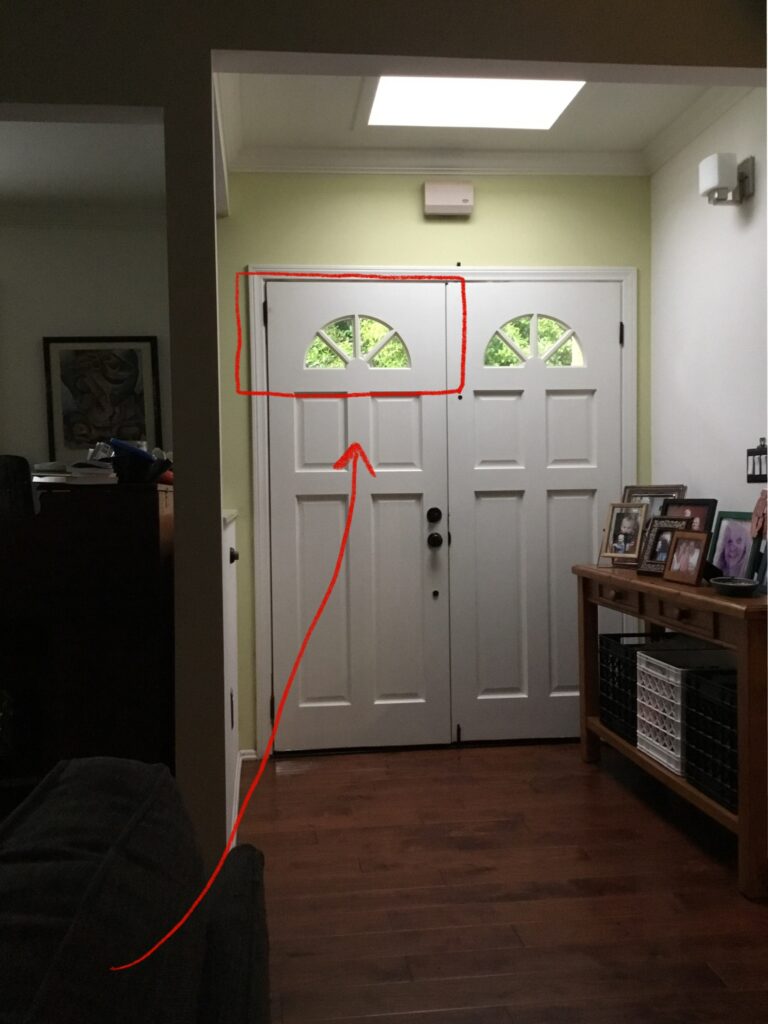

In this way, inner spaces become ontological. In his Spheres trilogy, Peter Sloterdijk defines human existence as “being in” a particular kind of space, “the place that humans create in order to have somewhere where they can appear as those who they are.” The sphere is his primary metaphor for the space which Being itself inhabits; it can be a womb, a house, a city, or a globe. In particular, “The sphere is the interior, disclosed, shared realm inhabited by humans—in so far as they succeed at becoming humans. Because living always means building spheres, both on a small and a large scale, humans are the beings that establish globes and look out into horizons. Living in spheres means creating the dimension in which humans can be contained.”

To understand something that “is,” to understand its “Being,” is to understand the space it inhabits and creates in relation to other beings. To change ourselves is to leave old spaces for new ones.

So, we are precisely the spaces we define and most importantly share with others. We share the womb with our mothers, we share our beds with our lovers, and we share our hideouts with our coconspirators. Our relationships are defined by the spaces in which we encounter one another. Spheres are imaginary spaces for “being in” together, and Sloderdijk works from “the hypothesis that love stories are stories of form, and that every act of solidarity is an act of sphere formation, that is to say the creation of an interior.” We not only understand “I” in terms of space, we understand “we” as well.

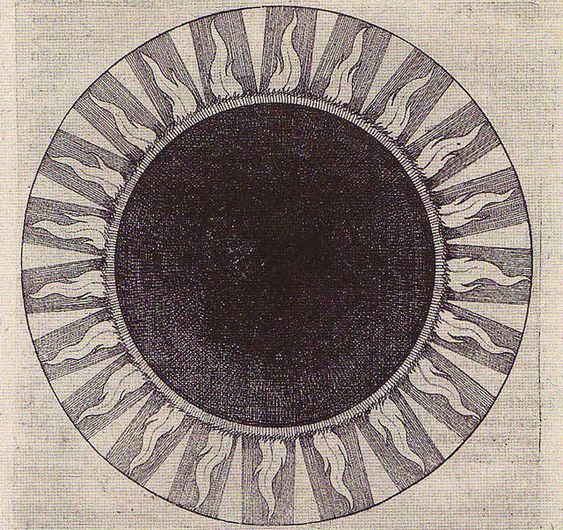

While I am sitting at the bottom of my imaginary well, I see myself as a kind of galaxy with a supermassive black hole at its center. I am its spiral arms and uncanny glow. This may seem inflated and preposterous, but consider the strange and sublime fact that within the vastness of outer space there is an infinitesimally small point in which all of that space is contained. Our own humble minds are just 15 centimeters long, but like jewels in Indira’s net, those tiny spaces contain reflections of an observable universe so large that fifty billion years of light could not trace its edges. The boundaries of space, as we understand them, are the boundaries of the self. To gaze above into outer space is always a gaze below too, into the inner spaces we build to hold our identities, our relationships, and our dreams.